Nuclear Astrophysics studies with HF-ADNeF

Understanding the origin of elements in our Universe

When we look at the world around us, it is full of a rich tapestry of different elements. We may very well ask ourselves where these elements come from? Models of the early Universe tell us that only hydrogen, helium and small amounts of other light elements are created in the Big Bang. Explaining where all the elements we see around us come from is a key area of nuclear physics known as nuclear astrophysics - the key insight is that is inside stars that the Universe creates a huge variety of different isotopes.

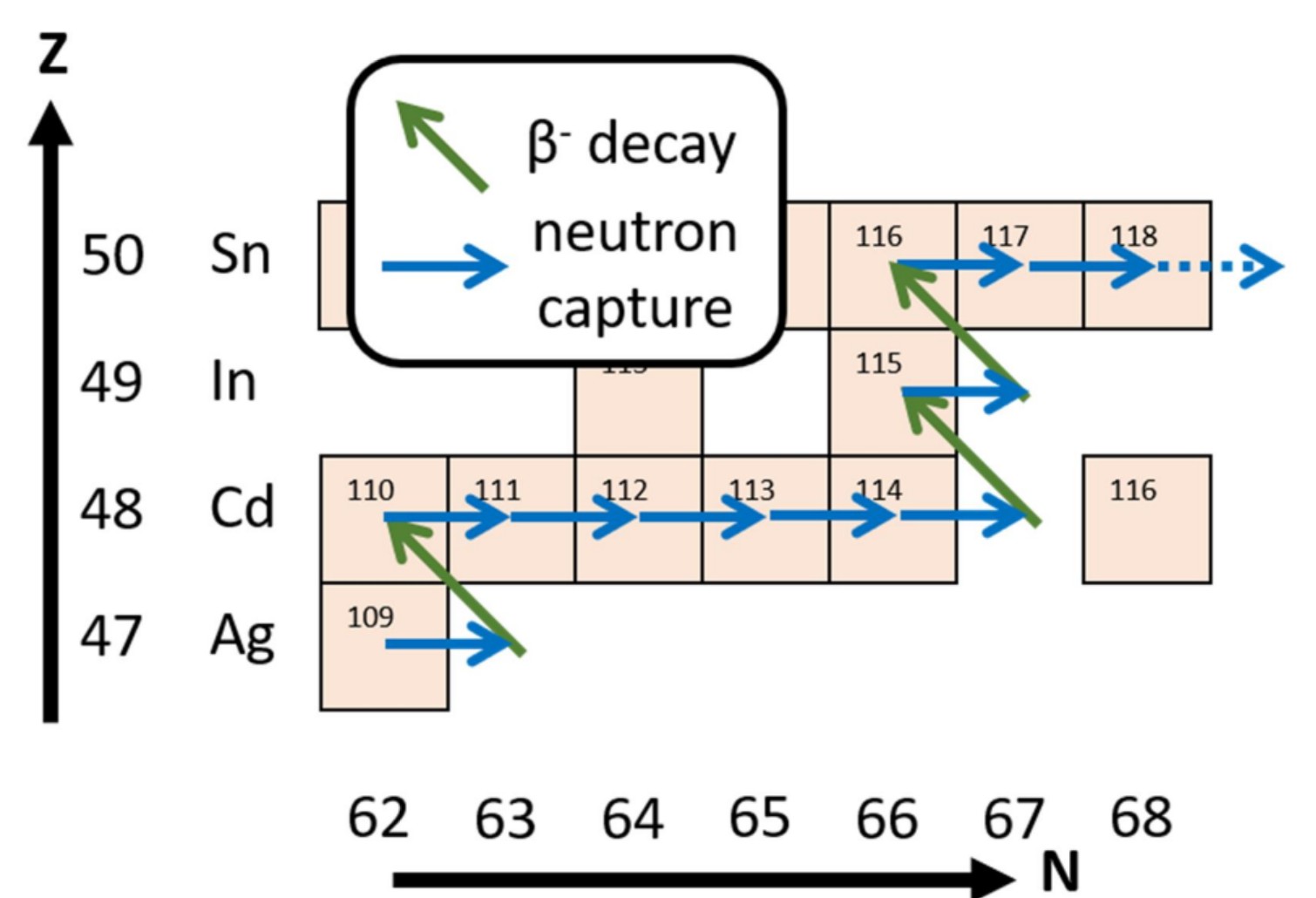

The fuel that drives stars to generate tremendous amounts of energy is (primarily) through nuclear fusion, joining together light nuclei to form heavier ones generates large amounts of energy. Eventually, fusing together lighter nuclei no longer becomes energetically favourable and around iron/nickel - fusion becomes an endothermic reaction. So how are heavier elements produced? The answer lies in neutrons that are also produced inside of stars. In the later stage of a stars life, when it is in the Asymptotic Giant Branch (AGB) stage, the heavy ashes sequentially absorb neutrons and then undergo beta-decay (converting the neutrons in the nucleus to protons). This is known as the s-process, seen below:

With a very high intensity of neutrons, we have access to directly measure these nucleosynthesis reactions here on Earth. This is a possibility with the Birmingham High Flux Accelerator-Driven Neutron Facility, HF-ADNeF.

The Birmingham High-Flux Accelerator-Driven Neutron Facility (HF-ADNeF) can produce up to 3 $\times 10^{13}$ n/s. We use those neutrons by bombarding a target which then absorbs the neutron, often making it radioactive. To understand the process of stellar nucleosynthesis, we need to know how likely it is for the different targets to absorb neutrons at different neutron energies. We call this probability, a cross-section. After blasting a sample with a large number of neutrons, we then stop the accelerator and take the radioactive sample to a highly-sensitive radiation detection such as a Hyper-Pure Germanium (HPGe) detector where was can measure the characeristic gamma ray fingerprints that tell us how much of the new radioactive species we have made.

More info here: (Wheldon et al., 2024).